Working Class Heroes

Working Class Heroes: Selected Film Posters and Stills opened yesterday at the AFL-CIO International Headquarters. This is the second exhibition I have organized for the AFL-CIO. The show was expertly, flawlessly installed by Nilay Lawson and Breck Brunson. It’s open Monday – Friday, 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, through November 15, 2009. The AFL-CIO is located at 815 16th St., NW (just north of Lafayette Park). Here’s some excerpts from the wall text for the show:

Working Class Heroes: Selected Film Posters and Stills opened yesterday at the AFL-CIO International Headquarters. This is the second exhibition I have organized for the AFL-CIO. The show was expertly, flawlessly installed by Nilay Lawson and Breck Brunson. It’s open Monday – Friday, 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, through November 15, 2009. The AFL-CIO is located at 815 16th St., NW (just north of Lafayette Park). Here’s some excerpts from the wall text for the show: Film is one of the most democratic arts. As German critic Walter Benjamin observed in his seminal 1936 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, cinema dispenses with the ‘aura’ of the unique work of art destined for elite connoisseurship. For the audience, there is no single ‘authentic’ Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times. Royals and workers, presidents and unemployed investment bankers see copies and one copy should be as good as another. Where reactionaries saw mass media as a looming threat to great culture, Benjamin welcomed it, arguing that the mass distribution of film, especially, would open the door to new content and eventually unlock art’s political potential.

Film is one of the most democratic arts. As German critic Walter Benjamin observed in his seminal 1936 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, cinema dispenses with the ‘aura’ of the unique work of art destined for elite connoisseurship. For the audience, there is no single ‘authentic’ Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times. Royals and workers, presidents and unemployed investment bankers see copies and one copy should be as good as another. Where reactionaries saw mass media as a looming threat to great culture, Benjamin welcomed it, arguing that the mass distribution of film, especially, would open the door to new content and eventually unlock art’s political potential. This exhibition of film posters and stills represents a wide range of Hollywood, independent and foreign films that incorporate workplace and organizing themes. In some ways, Benjamin’s prediction looks sustainable. Many of the films presented here have, in fact, helped bring public attention to important stories about worker safety, the exploitation of immigrant workers, impediments to achieving union recognition and other important issues. Many, but certainly not all, are also exceptional works of art.

This exhibition of film posters and stills represents a wide range of Hollywood, independent and foreign films that incorporate workplace and organizing themes. In some ways, Benjamin’s prediction looks sustainable. Many of the films presented here have, in fact, helped bring public attention to important stories about worker safety, the exploitation of immigrant workers, impediments to achieving union recognition and other important issues. Many, but certainly not all, are also exceptional works of art.In the process of selecting films for representation in the exhibition, one major theme quickly emerged: the celebration of the working class hero. The movies love heroes and in many of these films, especially Hollywood’s, the plot boils down to an individual’s battle with a hostile system, rather than true collective action. In that way, the depiction of workers shares a heritage with filmland’s other rugged individualists -- the cowboy, the secret agent, the detective, the lonely genius, etc.

Nonetheless, it’s a near miracle that some of these films were produced by business corporations. The profit motive surely plays a part (Norma Rae, Erin Brockovitch, for example, were box office hits). And, the power and progressive politics of stars (Meryl Streep, Jane Fonda) and directors (Mike Nichols, Steven Soderbergh) has been a key factor in moving working class hero scripts through a system that otherwise might not be sympathetic.

Nonetheless, it’s a near miracle that some of these films were produced by business corporations. The profit motive surely plays a part (Norma Rae, Erin Brockovitch, for example, were box office hits). And, the power and progressive politics of stars (Meryl Streep, Jane Fonda) and directors (Mike Nichols, Steven Soderbergh) has been a key factor in moving working class hero scripts through a system that otherwise might not be sympathetic.Most of the contemporary movies here are independent and foreign projects that have attracted distribution by virtue of their sheer quality (and the growing influence of festivals to get them off the ground). Not surprisingly, these films take a more nuanced view of the workplace. Indicative of the profound economic shifts experienced by workers in the last forty years, layoffs have been a major theme. Mondays in the Sun, Hula Girls, The Full Monty, and The Navigators all depict workers coping with closing factories and mines, declining job security, out sourcing and privatization.

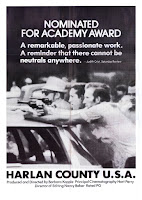

Still, the real complexity of organizing and collective bargaining mainly eludes the camera. The grit, drama and intensity of organizing campaigns and strikes is brought to life only in a few, most notably, Herbert Biberman’s Salt of the Earth (perhaps the most remarkable labor film ever made), and Barbara Kopple’s documentary, Harlan County USA.

Still, the real complexity of organizing and collective bargaining mainly eludes the camera. The grit, drama and intensity of organizing campaigns and strikes is brought to life only in a few, most notably, Herbert Biberman’s Salt of the Earth (perhaps the most remarkable labor film ever made), and Barbara Kopple’s documentary, Harlan County USA.

No comments:

Post a Comment